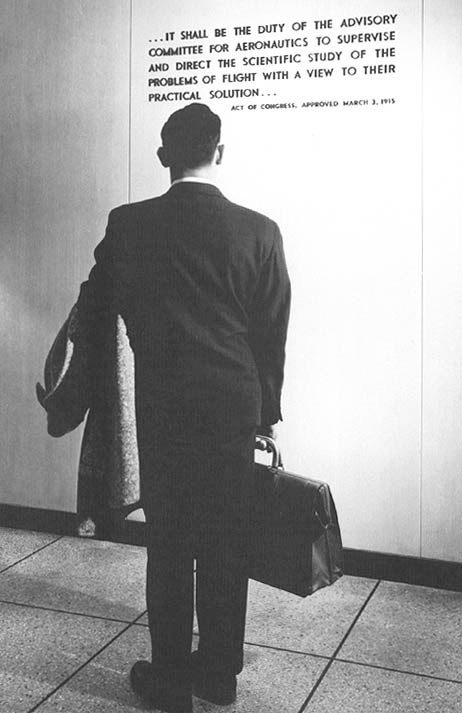

"it shall be the duty of the advisory committee for aeronautics to supervise and direct the scientific study of the problems of flight with a view to their practical solution"

From commons.wikimedia.org.

For most of the reviews of the NACA-era aircraft icing publications, I have tried to be neutral about whether one is "better" than another (they all have merit), except for noting how often they were cited and used later. This may have de-emphasized some of the biggest achievements, which are often not contained in just one publication.

NACA did not invent several of these items. NACA did find good ideas from many sources, and collaborated with industry, academia, and other government entities. They fulfilled their mission statement several times.

... it shall be the duty of the advisory committee for aeronautics to supervise and direct the scientific study of the problems of flight with a view to their practical solution ...

I have selected six "Crowning Achievements" of the NACA-era.

Two have received formal recognition in other sources (robust ice protection, the Icing Research Tunnel).

There are four others that I feel have been under-appreciated.

NASA SP-4306, "Engines and Innovations" 2 provides several observations.

Robust ice protection

One indication of the contemporary importance of the NACA efforts was the National Aeronautic Association 1946 Collier Trophy award to Lewis Rodert of NACA “For his pioneering research and guidance in the development and practical application of a thermal ice prevention system for aircraft.” 1

Note that the NACA efforts achieved complete, robust airplane ice protection. Protection for the wings and engines often gets the most attention, but flight in icing can quickly reveal other components that are not adequately protected, such as windshields, airspeed instruments, antennas, etc. See Component Ice Protection.

From NACA-TN-2569:

A total of 305 traverses of cumuliform clouds by P-61C airplanes were made in icing conditions, and on no occasion did ice accumulate before the end of a traverse to such an extent as to make safe flight impossible.

Cumuliform clouds are associated with a higher rate of icing call Intermittent Maximum Icing. Before the NACA efforts for ice protection, 305 traverses would have been fool-hardy.

It is notable that this was accomplished prior to the other achievements noted here. The was little knowledge of the icing atmosphere, as adequate instruments were not yet available. The Icing Research Tunnel was used, but it was found to not yet be adequate for the task. Ice protection thermodynamic analysis was developing at the time, but was of limited use, partly because the key values of icing conditions were not well known. Robust ice protection soon enabled advancement in other areas, particularly measuring icing conditions in flight.

The Icing Research Tunnel

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers recognized the IRT as an "International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark" in 1987 3.

Readers may be also interested in "We Freeze to Please": A History of NASA's Icing Research Tunnel and the Quest for Flight Safety, which has more information on the history of the Icing Research Tunnel.

The Icing Research Tunnel is still used today, for both research and industry tests. Numerous improvements through time have enabled an 80+ year life span.

The rotating multicylinder instrument

Without reliable instruments, one could not know what icing conditions are likely to be encountered, and reliable test and design could not proceed.

The rotating multicylinder instrument was assessed over and over again (that is why there is an entire Icing on Cylinders Thread with 17 posts). It was at times criticised, but there was no better instrument in the NACA-era (see the Conclusions of the Meteorological Instruments Thread).

Nobel Prize awardee Irving Langmuir (1932 for surface chemistry), together with Katherine Blodgett, put the analysis of the instrument on a sound theoretical footing. Even that was criticised, but more recent assessments show that the Langmuir and Blodgett analysis was accurate.

Thermodynamic models of ice formation

NACA progressed from the early, "cut-and-try testing of components" to "the design of heated wings on a fundamental, wet-air basis now can be undertaken with reasonable certainty."

From NASA SP-4306, "Engines and Innovations" 2:

Rinaldo J. Brun, William Lewis, Porter Perkins, and John Serafini produced a technical report [NACA-TR-1215] that calculated the impingement rate of cloud droplets on the rotating multicylinder. The report shows a solid command of boundary layer theory, heat transfer, experimental physics, and instrumentation that sets it strikingly apart from the simple empiricism of the reports of the mid-1940s. The discipline had indeed been placed on a rational basis.

The icing design requirements

It is difficult to design and test an ice protection system if the icing flight environment (liquid water content, water drop size, temperature, and other factors) are not well known.

From NASA SP-4306, "Engines and Innovations" 2 [emphasis added]:

In 1946 Lewis Rodert took charge of the icing program at the Cleveland laboratory. In a March 1947 memo, Rodert stressed the importance of gathering statistical data on icing clouds. These data would allow the Civil Aeronautics Administration to craft regulations to certify new aircraft if they met guidelines in providing ice-protection equipment. Reliable data were needed because of the "general disagreement over what constitutes a safe design basis for the heated wing." The Cleveland and Ames laboratories collaborated on this program.

By 1948 the program had logged a total of 249 icing encounters and had taken about 1000 measurements of liquid water content and droplet diameter. This was a collaborative flight research program carried out by the Air Force in the upper Mississippi Valley, by Ames in the West, and by Lewis Laboratory in the Great Lakes area. John H. Enders, an intrepid pilot from Cleveland's Flight Research program, flew the dangerous missions over Lake Erie, bringing back his Consolidated bomber encrusted with ice. In October the NACA group presented a tentative table of design conditions to the NACA Subcommittee on Icing Problems. This report defined the parameters for which icing protection was necessary for safe operation. The statistical data in this NACA report became the basis for the design criteria for federal requirements for aircraft icing protection adopted by the Civil Aeronautics Administration in the mid-1950s. In reflecting on the success of this effort, William Lewis wrote in 1969, "Considering the fact that we had data from 167 encounters in layer clouds and 73 in cumulus, statistical extrapolation to a probability of 1/1000 was more than daring, it was down right foolhardy" Nevertheless, more recent research using a much larger data base confirmed the conclusions of the 1949 report.

The "NACA Report" is NACA-TN-1855, the "much larger data base" is described in "Review of Icing Criteria" in 1969 Aircraft Ice Protection Report of Symposium (FAA).

The values determined by NACA are still in the current FAA icing certification regulations.

Icing design manuals

"Aircraft are now capable of flying in icing clouds without difficulty, however, because research by the NACA and others has provided the engineering basis for icing protection systems"

from The Icing Problem

The NACA tests, valuable though they were, would not be so useful if analysis could not fit the data.

From NASA SP-4306, "Engines and Innovations" 2:

To verify whether tests in the tunnel accurately reproduced actual flight conditions, the heat transfer data obtained by J. K. Hardy at Ames in his famous study of the heated wing were compared to tests on the same wing mounted in the icing tunnel. The data were in agreement.

The "famous study" was NACA-TR-831, the tunnel comparison was NACA-TN-2480.

Design manuals encapsulate the knowledge in reusable forms.

Fully half of the citations in FAA-ADS-4 “Engineering Summary of Airframe Icing Technical Data”, 1963 are NACA publications.

Conclusions

"... Before attacking what appeared to be a new icing problem we should study the icing work of the 1940's and 50's." 4

When I started blogging on this topic in three years ago, I had worked for 30+ years in aircraft icing, and I had several occasions to study the NACA icing publications in particular. I thought that I knew the publications well.

I was wrong. There is much more to be learned. As I studied the publications again, I often had thoughts similar to comments that the website "Blast from the Past: NACA Icing Publications" has received:

- "Stuff I was looking for"

- "it enlightened me a lot for my ongoing research"

- "an invaluable source of material"

- "I've been looking for that data point!"

Searching through and reading the NACA publications will reward you, at whatever stage of learning you are at.

The NACA publications are available at no cost at ntrs.nasa.gov.

Notes

-

Dawson, Virginia P. "Engines and Innovation: Lewis Laboratory and American Propulsion Technology. NASA SP-4306." Engines and Innovation: Lewis Laboratory and American Propulsion Technology. NASA SP-4306, by Virginia P. Dawson, 271 pages, published by NASA, Washington, DC, 1991 4306 (1991) ntrs.nasa.gov. ↩↩↩↩

-

Anon.: "An International Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark ICING RESEARCH TUNNEL", ASME, May, 1987. asme.org ↩

-

"Selected Bibliography of NACA-NASA Aircraft Icing Publications" ↩